Women are having a difficult time getting into treatment for opioid addictions, according to a Vanderbilt University Medical Center study published Aug. 14 in JAMA Open.

The “secret shopper” study used trained actors attempting to get into treatment with an addiction provider in 10 U.S. states. The results, with more than 10,000 unique patients, revealed numerous challenges in scheduling a first-time appointment to receive medications for opioid use disorder, including finding a provider who takes insurance rather than cash.

The situation only gets worse for women who are pregnant and addicted to opioids. Overall, pregnant women were about 20% less likely to be accepted for treatment than nonpregnant women.

“It wasn’t just that pregnant women had a hard time getting into treatment; everyone did. It was pretty extraordinary,” said Stephen Patrick, MD, director of the Center for Child Health Policy at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

“We have been in the middle of an epidemic of opioid overdose for years now. There are just too many barriers into getting treatment. We are still setting records levels of overdose deaths in the U.S., likely made worse by the COVID-19 pandemic. We know these medicines save lives; it shouldn’t be this hard to get them,” he said.

Providers in the study were randomly selected from government lists of persons providing either buprenorphine or methadone treatment for opioid addiction.

Medications for opioid use disorder such as buprenorphine, most commonly received from providers in an outpatient clinic, and methadone, received in an opioid treatment program, have been proven to reduce overdose risk and improve pregnancy outcomes for patients, Patrick said, including a reduction in the risk of preterm births.

A total of 10,871 unique patient profiles of pregnant vs. nonpregnant women and private vs. public insurance were randomly assigned to 6,324 clinicians or clinics.

About a quarter of the time, callers tried at least five times to reach a provider without success; another 20% of the time they reached a provider who didn’t provide addiction treatment.

“For women trying to get into treatment, just getting someone on the phone proved to be a challenge,” Patrick said. “Only about half of the time – if they actually reached a provider – were they able to make an appointment for treatment the first time. “

A large portion of the clinicians from 10 states did not accept insurance and required cash payment for an appointment.

“Only about half of women were given an appointment for treatment with their insurance, the rest were either told no or had to pay cash. In some states, only about 1-in-5 women were given appointments with their insurance,” Patrick said. “That’s really staggering. You are telling folks in the middle of an epidemic, folks who are disproportionately impoverished, that you need to get into treatment. But then most providers either say no or don’t take any insurance.”

Insurance was not accepted by 26% of buprenorphine prescribers and one-third of the opioid treatment programs in total. Median out-of-pocket costs for initial appointments were $250 for buprenorphine prescribers and $34 for methadone prescribers.

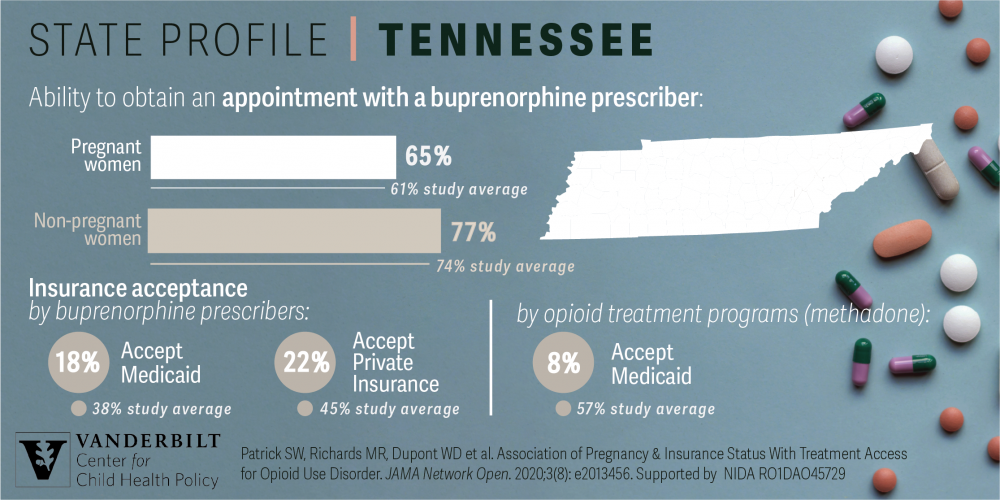

Overall, about two-thirds of callers were able to make an appointment (67.6%) with outpatient buprenorphine providers, but pregnant women received an appointment only 61.4% compared to non-pregnant women at 73.9%.

For opioid treatment programs about 9-in-10 callers were able to get an appointment and there was no difference between pregnant and non-pregnant women.

“We found that opioid treatment programs took pregnant women at the same rate that they took nonpregnant women. That is not true for buprenorphine providers,” Patrick said. “It is also important to note that opioid treatment programs are far rarer than buprenorphine providers.”

Patrick said the study results should serve as an immediate call for policymakers to intervene.

“Reducing barriers to medications for opioid use disorder has been identified as key public health goal by the U.S. Surgeon General, the President’s Commission on Opioids, but our research suggests substantial barriers remain,” said Patrick.

“We need to begin to put systems in place where people can get the treatment they need when they want it. For pregnant women, not only does it save their lives if they get this medicine, but it also makes it more likely that their infant is going to be delivered at term.”

The study was funded by the National Institute On Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DA045729. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.